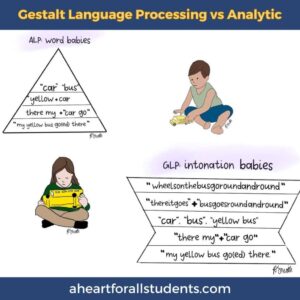

Gestalt language processing, Natural Language Acquisition, echolalia, and scripting—it’s the hottest topic in the SLP-verse. But what does the evidence say? Gestalt Language Processing (GLP) is a language development style that is characterized by children learning language as scripts, which are whole phrases or chunks of language. GLP is a top-down style, where words or phrases are learned as complete units. This is different from the traditional model of language development, which is bottom-up. Many autistic individuals are Gestalt language learners, but not all Gestalt language learners are autistic. And there are children that may process language in both ways.

Quick answer—yes, partly…it’s complicated! So while we wish we could pull this off in a quick soundbite, you’re going to need to grab a chair or an earbud and settle in for the ride. Let’s go!

What is GLP and where did it come from?

Gestalt (guhSHTALT or /gəˈʃtɑlt/) comes from the German word meaning “form” or “shape.” Within psychology, it refers to processing information (visual, auditory, linguistic) as a whole that’s more than the sum of its parts.

In language, a gestalt is a multi-word “chunk” that a speaker hears, stores, and uses as a whole, before having knowledge/awareness of its internal structure. It may be defined by its prosody/intonation and have an idiosyncratic meaning related to a specific context where the person has encountered it. It may or may not be intelligible to the listener. You might have learned sentences in a foreign language as gestalts, understanding the sense of the whole meaning within a context, but not the individual words and how they fit together.

A person communicating with gestalts can also be described as using delayed echolalia (a more common term in the literature, most often in reference to autistic people). “Delayed” here means the person is echoing an utterance after a gap of time and not immediately after hearing it. Scripting is sometimes used synonymously with echolalia, but can also refer to the use of learned chunks of language as a consciously applied communication strategy (e.g., memorized answers to interview questions or those classic small talk rituals); “scripts” are not necessarily gestalts.

Gestalt language processing was named and described by the linguist Ann Peters in her 1983 book (a compilation of qualitative research) and taken up by SLP scientist Barry Prizant (who you may know from Uniquely Human and the SCERTS model) and colleagues. Much of this work is several decades old. This is a model of language acquisition where a child acquires gestalts as their initial units of language, which they then can learn to break down (“mitigate”) later. You can think of this as the “large-to-small” route to developing productive grammar.

Prizant described four fluid stages of gestalt language acquisition in his subjects:

- Echolalia [“I love you, you love me”- Nursery rhymes and songs for young children]

- Mitigated echolalia [“I love Dad, Dad love me”]

- Isolated words and beginning word combinations [“love puppy”]

- Grammar [“I love this”]

GLP is contrasted with analytic language processing, the “typical” language acquisition path we all learned about, which starts at the single word level and builds to phrases and eventually sentences—the “small-to-large” path to grammar, which gestalt language acquisition reaches at the fourth stage.

The theory wasn’t that people use all gestalt or all analytic processing, but rather a blend of the two, and that a subgroup of people (including but not limited to many autistic people) might rely predominantly on gestalt processing. The idea is that you need both routes to explain typical language acquisition, and that both represent “normal,” developmental progressions, each of which would need to be considered in language assessment and intervention. While a language delay in a mainly “analytic processor” might look like a small repertoire of single words at age two, a delay in a mainly “gestalt processor” would just look like echolalia.

To add more terms to the mix, you may have heard of Natural Language Acquisition (NLA), which is the specific work on gestalt language by SLP Marge Blanc, laid out in her 2012 book and seminars. She expands Prizant’s four stages of gestalt language learning to six (adding stages for advanced grammar) and sets out a language sampling protocol to track an individual’s operating stage(s) and grammar development using Laura Lee’s developmental sentence types and developmental sentence scoring.

GLP and autism

While it is suggested that many people (neurotypical and neurodivergent) use gestalt processing either partially or predominantly, GLP is most often discussed in reference to autistic people. Echolalia has been associated with autistic people since autism was first described, but often through an ableist lens, where it was often seen as noncommunicative and addressed (i.e., extinguished) through behavioral approaches. Through a GLP lens, echolalia is communicative and the first step in that individual’s “natural” development of language.

Confusingly, if you’re googling around you’ll see things saying autistic people may have impaired gestalt processing. This is using the word in a different way, referring to situations where people perceive and remember many fine details while not getting the “big picture”—not seeing the forest for the trees.

What’s different about a GLP/NLA approach to language intervention?

Most of the therapeutic principles are what any good responsive therapist would do and teach:

- Building a genuine connection with the child and following their lead/interests

- Noticing and honoring communication attempts and their underlying functions

- Building on the current language system with individualized, meaningful targets

- Tapping into caregivers’ expertise and working collaboratively

- Inclusion of self-regulation and sensory strategies as needed for the individual

The key practical differences between a GLP/NLA approach and therapy-as-usual come in with how you approach assessment (with reference to the four/six stages) and then what language units you target, including, at the early stages, supplying the child with new gestalts that will be meaningful and easy to mix/match late. A frequently suggested early gestalt is “Let’s ____”. The thought is that stages generally aren’t/can’t be skipped, since grammatical development requires single words, and proponents say a child using mostly non-mitigated gestalts needs to start by mixing and matching chunks of scripts before you can work on single words.

We can contrast this with:

- Approaches that teach new scripts as “functional language” or “survival phrases” (think: “I need to use the bathroom, please”), but without considering them as a stepping stone to grammar; and

- Core word approaches that consider teaching single, high-frequency words (and then combining them) as the surest path to robust language skills.

There is, of course, a huge, philosophical difference between all of these approaches just mentioned and ones that—wrongly and harmfully—see echolalia/scripting as meaningless or treat it as something to simply eliminate for the comfort of others or to allow the person to appear more neurotypical—i.e., teaching them to mask.

Okay, cool. But is all of this EBP? What does the evidence say?

Let’s break it down, EBP-triangle style!

Client/family/community values and expertise: This gets into why GLP/NLA is *everywhere* right now. These ideas and the work they are based on aren’t new, but what’s changed recently is a GLP explosion with SLP influencers and content creators on social media.

Approaching echolalia functionally through the principles of GLP/NLA, which not only normalizes but values the functions of echolalia and scripting, fits that bill. Caregivers and therapists are also finding that the concept of gestalt language processing “clicks” with their knowledge and observations of their children/clients and gives them a path forward. Finally—and critically—we’re hearing first-person accounts from autistic people that it describes their own experiences of learning language.

Clinical evidence and expertise: Marge Blanc’s book includes extensive longitudinal language samples demonstrating her autistic clients’ progression through the stages over time given GLP-based intervention. She elected to publish these in a book geared toward caregivers instead of a peer-reviewed publication.

Then, the thing that probably brought you here in the first place…

External research evidence:

First, let’s acknowledge that there are hefty barriers to clinical research on delayed echolalia. While some scripts are easy to ID (think: the kid who can perform whole episodes of Barney, or our staffer V. Tisi’s client who calls cake “happybirthdaytoyou”), some are really, really not, even for familiar listeners. Language sampling in these cases is not an exact science, which is a challenge in the context of… well, science. This is why the work to date in this area has been qualitative, instead of quantitative in nature. With that in mind, here’s the rundown on the evidence we have—and don’t.

What we know:

- Echolalia serves many communicative functions (see Prizant & Rydell, or Stiegler for a more recent review).

- Scripting is a valid/important form of autistic communication. (For a great overview that centers autistic voices, check out this dissertation from Colleen Arnold. It’s a good read!)

- First- and second-person accounts of some autistic people’s language development align with a gestalt language model (with some, like that of dad Ron Suskind reaching popular culture).

What we don’t know:

- It’s unclear whether it even makes sense to talk about kids as either analytic or gestalt processors because it’s probably not really that clear-cut. Prizant and Peters both specifically deny suggesting an absolute split between the two “styles”, saying that most people likely use a mix of both, with one being predominant for some. Accordingly, there are no clear criteria for designating someone a gestalt processor, and we can’t assume that all autistic children are. Forcing a dichotomy in our thinking and practice may not benefit our clients, but recognizing that both types of processes are possible is important.

- For those children who do appear to communicate through gestalts, we don’t have controlled studies comparing interventions with the goal of transitioning those scripts into flexible language. So, while expert opinion and clinical experience can offer a starting place for approaching an individual case, our critical thinking and assessment of the child we’re working with might take us in different directions.

- The linguistic stages are a useful descriptive framework, but we don’t know whether they represent something “real” in the brain, how many autistic people’s language may really follow the “textbook” progression, or whether using a word-based approach may be more successful for some learners.

- We don’t know how best to integrate a gestalt language approach with AAC and emergent literacy teaching, so navigating those intersections calls for a lot of clinical judgment, as well as considering the input of AAC users and the autistic community.

Cautions:

- Watch out for stats that sound official: we’ve seen everything from “50% of children are gestalt language learners” to “75–85% of autistic children are gestalt processors.” Given the lack of evidence for these numbers—and the reality that there’s no clear-cut way to designate a child as gestalt vs. analytic vs. somewhere-in-between anyway!!—these estimates shouldn’t be broadcast as facts.

- Be aware of potentially harmful generalizations, including those about typically developing boys frequently being gestalt learners.

- The idea of learning styles, and of people using left/right brain strategies, come up in discussions of GLP. This is considered a neuromyth.

Some final thoughts

The idea of gestalt processing has the ingredients for being a useful model for approaching the assessment and treatment of some individuals who communicate through echolalia. Models are helpful to the extent that they capture/explain specific observations about the world (or in this case, about an individual’s language system) in an easy-to-understand way and provide testable predictions that can be supported or undermined through data collection (aka longitudinal language sampling). But without a lot more data, a model is just a model, like those styrofoam-ball solar systems you maybe made in school. They don’t explain everything—and weaken if we overextend them—so notice if you are doing lots of mental gymnastics to make things fit the model that would be better explained another way.

As these ideas continue to filter through the field, we’re likely to see oversimplifications and other problematic applications of these concepts to practice. Watch out for quick fixes: an approach that requires deep knowledge of the child and their language environment, extended language sampling and analysis in collaboration with familiar listeners, and individualization of targets and therapy is tough to translate to, for example, a school caseload and timelines, and people will be apt to look for shortcuts that don’t align with evidence.

You do not need to be specially certified to begin practicing using these principles—NLA is a protocol, but the concepts behind it are not owned by any single person or program.

It can be tough to know whether or how to integrate “new” ideas into our practice, especially when we see them coming primarily from a single source, or a group of people who are all professionally associated with one another. As always, we have to:

- critically consider the implications of shifts in practice,

- question our (and others’) assumptions,

- avoid repeating unproven claims as facts, and

- keep individual clients at the forefront of our minds.

This article has been adapted from the Informed SLP. Follow link for a A community for adult Gestalt Language Processors.